When they first met, she thought he was a knight in shining armor. He took her out to eat at nice restaurants, bought her presents, made her laugh. She quickly fell for him, and he said he loved her.

He loved her so much he wanted to know her where she was and who she was with at all times. Then he started telling her what to wear, what to eat, how to spend her money—but only because he wanted the best for her.

When they watched television together, he always turned on sports because he couldn’t stand those “girly” shows. He asked her not to see her friends anymore because they were a bad influence, and she was better than them.

The first time in months she was allowed to go out with her friends, his text messages and phone calls were incessant; he even showed up at the restaurant to check on her. He swore he only did it because he was worried and loved her that much.

She begged him to go visit her family, but he refused. He started yelling at her for being ungrateful and accused her of cheating. When she didn’t answer her phone fast enough, he became furious and he called her names: thot, whore, bitch, slut. Then he begged for her forgiveness and said he didn’t mean it; jealousy got the best of him; he would kill himself if she left; it would never happen again.

Until it did happen again, and again, and again. He just loved her so much.

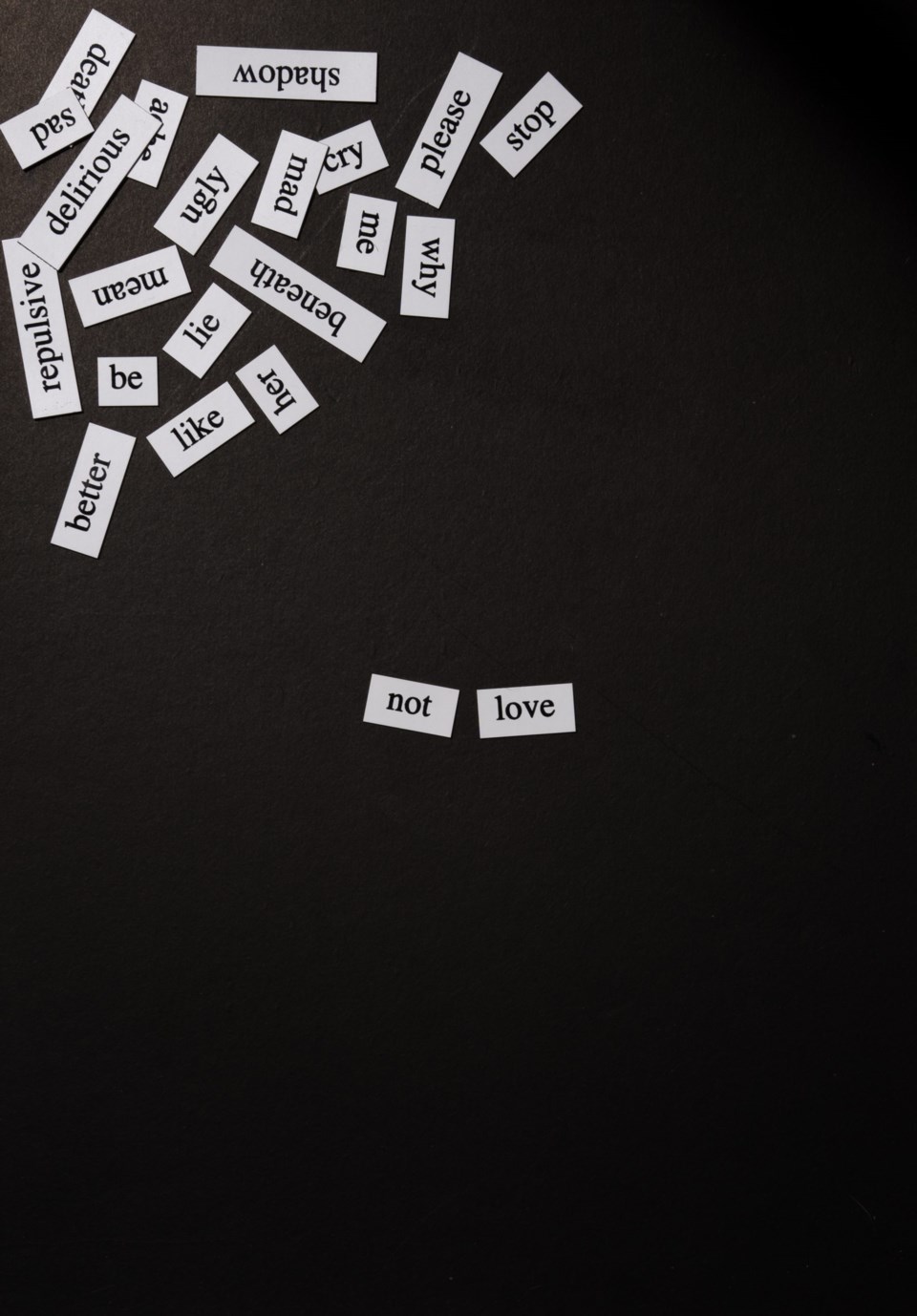

That’s not love. It’s emotional abuse.

What is verbal and emotional abuse?

Emotional and verbal abuse can be difficult to recognize, especially for the victims. There are no cuts or bruises, and it often happens under the disguise of protection. Nearly half of all women and men in the U.S. have experienced emotional and verbal abuse by an intimate partner in their lifetime according to the National Domestic Violence Hotline.

Emotional abuse, also known as psychological abuse, can be defined as any non-physical behavior or attitude that is designed to control, subdue, punish or isolate another person through the use of humiliation or fear. It can include: verbal assault, dominance, control, isolation, ridicule or the use of intimate knowledge for degradation, according to Dr. Diane Follingstad, a leading researcher on violence against women at the University of Kentucky. It is often a precursor to physical and sexual abuse.

Mary White is a counselor at Agape Resource & Assistance Center, a nonprofit in Plano that provides housing and teaches life skills to women who are victims of abuse.

“[Emotional and verbal abuse] start very subtlety,” Mary says. “There’s a grooming period. [The abuser] seems to do and say all the right things. If the relationship starts really deep and really fast, that’s a real big red flag. Getting into [an exclusive] relationship should take time.”

“Abusers say, ‘It’s because I love and want to make sure you’re safe,’” Cynthia Garrison, program director at Agape, says. “They twist it to make it sound good, but it’s a way to control [their partner].. We all want that connection with someone—that love. [The abuser] finds that vulnerable spot, and they exploit it. ‘Sticks and stones can break my bones but words will never hurt me.’ That is not true. Words and emotional abuse can hurt worse especially over time. It messes with your mind.”

Emotional and verbal abuse isn’t always easy to detect; it can be portrayed as normal behavior, and even glorified in books, movies and television shows. For example, in Stephanie Meyer’s popular Twilight series, Edward, the protagonist, constantly watches and follows Bella, the woman he loves, and controls her every move in order to “keep her safe.” Other toxic relationships include Chuck and Blair from Gossip Girl, almost any relationship on the reality show Jersey Shore, and Belle and the beast from Beauty and the Beast.

Emotional abuse doesn’t happen strictly within romantic relationships. It can be a student and teacher, like in Whiplash. It can be a parent and their child.

“I didn’t allow [my kids] to watch Hannah Montana,” Cynthia says, “because she was very disrespectful to her father. It was verbal abuse, even though it was a daughter to a dad—[the abuse] was allowed.”

Victims are often manipulated into believing the abuse is their fault or that it didn’t even happen, Mary says. This form of manipulation is called gaslighting, and through persistent denial, belittling, lying and other strategies the abuser attempts to destabilize the victim’s belief in their own sanity.

“The interesting thing about gaslighting is women tend to think, ‘Am I wrong? Am I going crazy?’ Abusers make you think you’re the one with the problem. It’s important for all women to understand that love is not about someone trying to control you, trying to tell you how to live your life. You should be able to do the things you want to do, like go out with your friends,” Mary explains.

For Cynthia, psychological abuse is particularly frightening. “It’s scary because it shows how manipulative people can be and how [easily] people can be manipulated without knowing it, without seeing the signs. [Victims] can be brainwashed. Often an intervention has to happen before they realize [they’re being abused], and sometimes they don’t realize until they’re so far into it that a lot of damage has happened,” she says.

Sometimes, victims of emotional abuse grew up with abusive parents who screamed at them and called them names. Because that’s all they have ever known, the victim is conditioned to believe that abuse is love, Mary says. This can lead them to allow emotional abuse from not just romantic partners but coworkers, bosses and friends.

“There’s this area of grayness: do I let my child have freedom and learn about life, or do I stay on top of them and control them? Our job as a parents is to work ourselves out of a job. Unhealthy parents are still right there controlling everything about their child. Now that’s who [their child] gravitate towards in their adult relationships,” Cynthia explains.

“As a parent you have to think of your motives behind your behavior. You have to ask yourself: What’s going on here, and what am I afraid of? A lot of [abuse] is fear-based, behind all the anger and aggression,” Mary says.

Escaping the abuse

The Institute for Urban Policy Research (IUPR) at UT Dallas (UTD) released their annual study on domestic violence in Dallas this past November, which reported on domestic violence-related incidents from June 2016 to the end of May 2017. During that time period, more than 15,500 domestic violence offenses were reported to the Dallas Police Department, and nearly 8,000 victims were turned away from shelters due to lack of space. On average, shelters in the Dallas area are at 100 percent capacity at all times despite increases in space.

In 2013, Sarah Nejdl was so shocked by the UTD study she founded Families to Freedom, a North Texas based nonprofit whose mission is to help victims of abuse get to shelters in another county or with family that lives in the U.S. They specialize in long distance travel by providing people with bus passes and gas cards or having a volunteer drive them. Families to Freedom is the only nonprofit geared towards long distance travel for abuse victims in the country.

“Not everybody gets shelter when they call, and that can keep someone in an abusive relationship,” Sarah says. “Imagine, you’ve been told [a certain place] is a great shelter. You finally get the courage to call, and that shelter says, ‘I’m sorry we don’t have room.’ It doesn’t matter how urgent her situation is; if there’s no room, there’s no room. I think women who get turned away from shelters think, maybe this isn’t my day, maybe I made a mistake. It’s a sign that they shouldn’t leave.”

Sarah says Families to Freedom never turns away someone who calls them. “We find a solution for everyone, even if I get in the car to drive her,” she says. While they try to help everyone, not all victims meet the criteria to travel a long distance. They have to see a civic professional, like a counselor, doctor or police officer, to confirm that they’re truly in need of help, and they have to be mentally and emotionally ready to leave their abuser.

“When we pick someone up they may be anxious, nervous, sad, depressed—it’s a big day for change,” Sarah explains. “The farther away we get [from the abuser] the more we notice her relax. As we get closer to the destination there is a variety of new emotions: joy, happiness relief, tears. The best is when we get to the family’s door; they come out, everyone is happy—it’s like a family reunion.”

Rarely do any of Sarah’s clients change their mind about leaving. One trick her drivers use is a playlist of empowering songs like “Never Ever Getting Back Together” by Taylor Swift, “Survivor” by Destiny’s Child and Beyoncé’s “Run the World (Girls).”

“They doubt themselves, and that’s a normal human emotion. We try to help eliminate some of that doubt during the road trip,” Sarah says. In 2017, Families to Freedom helped [457] adults and children find a fresh start.

Read more: Almost Gone: A Plano family’s close call

A new normal

While working with clients, Mary often witnesses an “a-ha” moment; a light bulb goes off in their head and they finally recognize the abuse for what it truly was. A big part of getting victims to that point is helping them feel safe and that they aren’t alone.

“It’s a new normal [for them] to feel safe and understand that they have a right to say no and learn healthy boundaries. When we gather the women [of Agape] together and they talk in their group counseling sessions, it’s so powerful when they tell their stories. Then they say, ‘Wow that was me. I went through that too.’ That sisterhood is very important. They are resilient and strong; they’re relearning that they have rights and a voice,” she says.

Mary also uses art therapy which helps women express feelings they don’t have words for, but often helping these women adjust can be as simple listening.

“When you give women a platform to tell their story and believe them—that is powerful. For so many of our women, their children are their biggest motivator. They want their kids to have positive life experiences and that propels them to get out of an abusive relationship,” she says.

“It’s neat to see that transition,” Cynthia says, “but we have to make [Agape] a safe—not a controlling—place. It’s not our goals, it her goals. I have to make it safe for her to say, ‘I don’t want to do this the rest of my life. I want to do this.’ If they’ve been controlled for so long they feel like they can’t make simple choices, like what they want for dinner. I have to make it safe for them to push back, to say no, and they won’t be shamed for disagreeing with me.”

“Love is patient and kind; love does not envy or boast; it is not arrogant or rude. It does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable or resentful; it does not rejoice at wrongdoing, but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres.” 1 Corinthians 13:4–7.

Nearly all of us have heard this passage at some point, but just because we know it doesn’t mean we’re immune to emotional and verbal abuse disguised as love. According to the National Domestic Violence Hotline, more than half of college students say it is difficult to identify dating abuse and that they don’t know what to do to help someone who is a victim.

If you believe you have a friend in need of help, Mary says to not place blame or guilt on them. Instead, listen without judgement and empower your friend. Help them make a safety plan by establishing people and places they can call if they need immediate support.

“It is important that you not tell the survivor what to do or when to leave,” Mary says. “Don’t try to find a quick solution without thinking through the potential retaliation from the abuser. If your friend decides to stay in the relationship, continue to be supportive. It might take several incidents before they leave the situation. As they become more aware of their unhealthy the relationship, your continued love and support is crucial.”

Trained advocates are available to take your calls through the National Domestic Violence Hotline toll free at 1-800-799-SAFE (7233) or call 2-1-1 for local shelters and resources. Find more information at familiestofreedom.org and hope4agape.com.

Originally published in Plano Profile’s February 2018 Issue.