The first time I met Benny Parkey in early 2015, he was dying. The former Denton County sheriff, who had garnered a reputation as “the bulldog,” had put up a hell of a fight against stage 4 lung cancer, making monthly, then weekly, visits to drain the excess fluid from his lungs. The new year had come and gone. Trump was on the rise, and Benny was reaching the end of his road. A gruff-looking older man, with more gray than brown in his hair and beard, he was a martial arts master and a decorated lawman who’d been battling cancer for several years.

But he had one more task to accomplish before he died: unseating the sheriff who beat him in 2012, the same year he was diagnosed with lung cancer.

Benny saw his chance after he read a few articles I’d written about his former opponent, Sheriff Will Travis, for the Denton Record-Chronicle. He called the newsroom, and we met at a coffee shop on the outskirts of town. He brought a few documents, showed me a couple of old news articles about Travis’ separation from the DEA, and shared some insider law chatter. He mentioned Travis’ ex-wife, who was growing more frustrated with her ex-husband’s inability to shut up about their relationship on the campaign trail.

Squaring off against the sheriff incumbent in Denton County isn’t a feat for any candidate to take lightly. There, the sheriffs have been known for fishing with dynamite and running the sheriff’s office like a personal fiefdom. Digging up dirt on the top lawman in the county is a surefire way to land yourself six feet in the ground or at least wish you were there.

“I’m an old man dying of cancer,” Benny said, watching the sunrise. “Nobody gives a shit. I don’t care. I get to voice my opinion. What’s going to happen to me? They can’t kill me.”

Benny fell quiet, no doubt swimming in his past. I didn’t disturb him. I simply drank my coffee, smoked a cigarette, and itched to return to the newsroom to delve into the documents.

“I didn’t campaign as hard as I could have,” he said. “I was otherwise occupied. I couldn’t get out on the weekends, honestly. I had friends that did. And god bless them. That’s what I’m talking about. I don’t want to say that I couldn’t do it because my wife was sick. That’s not right. I was otherwise occupied. My energies were split.

“When he ran against me, it looked like he was running for Congress,” he continued. “He had TV ads, every day at noon and 6 o’clock. Half of the county didn’t know me, him or anybody else. But they knew their history. ‘Remember the Alamo—Will Travis.’ ‘Oh yeah, I remember.’ It was another big hurdle.”

Nearly everyone who’s attended school in Texas knows the Alamo hero William Barret Travis. The state requires students to start learning about him in the seventh grade. He penned the 1836 Victory or Death letter, surrounded by Santa Anna’s forces. “I shall never surrender or retreat,” he wrote, and students remembered. Sheriff Will Travis read the legendary letter when it returned home to the Alamo a couple of years after he defeated Benny.

“But now he’s had three years to make an ass out of himself,” Benny said, “and everybody knows he’s made an ass out of himself. I dare you to find one law enforcement professional who will support him. Just one.”

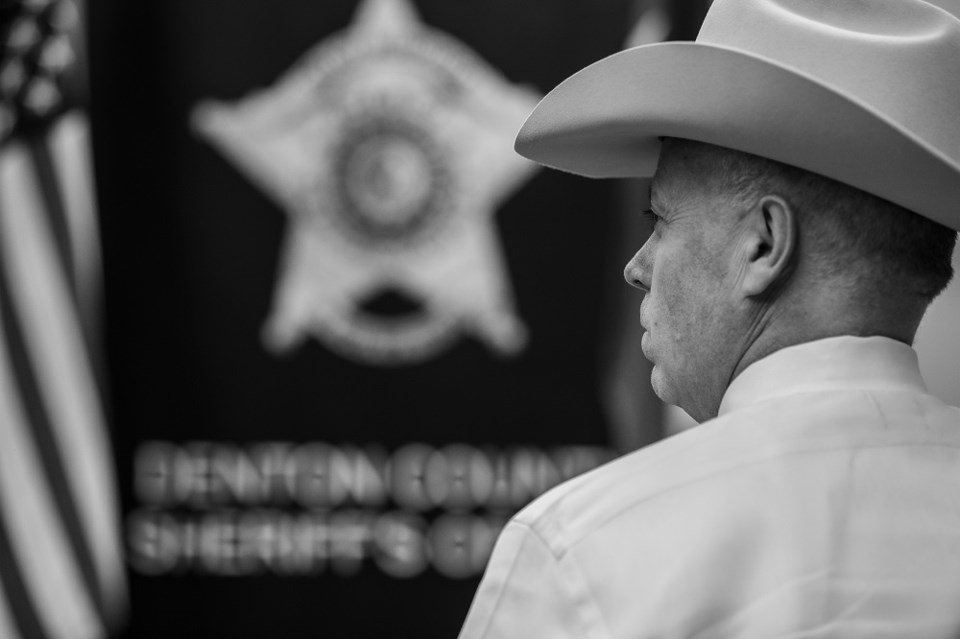

A former employee, a retired Texas Ranger, Tracy Murphree blazed onto the scene in a white cowboy hat. He promised to bring a Ranger’s integrity back to the sheriff’s office, and “Murphree for Sheriff” political yard signs began appearing in lawns around the county. “No man in the wrong can stand up against a man who’s right,” Murphree would say on the campaign trail.

A brutal campaign battle between Murphree and Sheriff Travis only grew worse as my investigation unfolded. In early February 2016, shortly before the Republican primary, I published a story about Travis and his exploits as a DEA agent in the ‘90s. There were allegations of fabricating evidence and relations with both a confidential informant and a nanny not yet out of high school. Travis denied the allegations, but his political endorsements fled like rats from a burning dump. A month later, a surge of them (about 96,712 of them total) shattered records when they hit the ballot box. Murphree was elected the next Denton County Sheriff. Benny had gotten his wish, and said he could die a happy man. “You’re a fine investigator,” he told me at Murphree’s election night watch party.

Four years later, Benny is dead. Sheriff Murphree is seeking reelection, facing not one but two opponents who appear as good as he does on paper. Bryan “Wilkie” Wilkinson, a sniper trainer, an active shooter awareness guru, is Murphree’s former employee and promises to bring a Benny Parkey-kind of change in leadership to the sheriff’s office. Dugan Broomfield wears a white cowboy hat like Murphree, but isn’t his former employee. His wife is. She retired last year. “I’ve alway thought about running for sheriff,” Broomfield says. “Kenny Lemmons is running for his fourth term in Clay County, and Ed Daniels was the sheriff of Archer County. One of my guys went back home to Seymour and Baylor County and was appointed as sheriff there. So I’ve always wanted to do it.”

Broomfield and Wilkinson mostly disagree with Muprhree’s “One riot, one Ranger” style of leadership. Strict and rigid, it’s not known for encouraging constructive dialogue. It’s more of a “it’s my way or the highway” frame of mind. “There is a revolving door [at the sheriff’s office],” Wilkinson says. “They come in, and then they’re out.”

Both of Murphree’s opponents claim a mass exodus has occurred. Murphree, they say, has obliterated morale, causing a walking-on-eggshells environment. Employees are leaving, some to the greener pastures of the suburbs where police departments pay $20,00 to $40,000 more than the sheriff’s office. Broomfield, though, claims it isn’t just about the money. “The guys in the jail and the patrol guys are not appreciated as much,” he says. “A lot of them are quitting before they thought about leaving. And that is sad. They want to stay here, but it gets so bad here.”

In “Why Tracy Murphree Should Be Replaced As Denton County Sheriff,” former Denton County Sheriff employees and volunteers bemoan Murphree’s oppressive culture of retaliation and forced resignations and question his refusal to join Collin County Sheriff Jim Skinner’s North Texas Criminal Interdiction Unit, a task force he created with seven other sheriffs, including Wise County Sheriff Lane Akin, a retired Texas Ranger. They have a multi-agency jurisdictional agreement, which allows them to operate in each member’s respective county. Denton County is the ideal partner since it is located between Wise and Collin counties. But three years have passed, and Murphree still hasn’t joined the unit. It’s something both of his opponents propose to do if elected sheriff.

“It’s common to hear among experienced deputies and others within the Denton County law enforcement community, ‘If I’d only known, I’d have voted for Will Travis,” the former volunteers point out.

When I first met him at a coffee shop in early 2016, Benny didn’t look like a clean cut member of the law enforcement community. He reminded me of Obi-wan Kenobi sipping coffee in the Tattoonie suns’ early morning light. His hair and beard were longer, more white than brown, and he smiled more than he frowned, especially when he discussed his past. He’d been contacting me like Deep Throat from the X Files for a year now, dropping clues and information that Travis denied and, in some cases, blamed former Sheriff Weldon Lucas, a retired Texas Ranger who faced Travis in the early 2000 elections. Lucas ran his office under the “One riot, one Ranger” leadership style, and was accused of keeping black men and most women from rising through the ranks. The Dallas Observer called him a political kingpin and “The Untouchable.” He’d been known to have his underlings give reporters manila envelopes filled with Travis’ skeletons. “Make sure they know I’m the one sending it,” he’d say.

With the legendary Alamo hero’s name, Travis had become a political kingpin in the years since Lucas’ death in 2011. He reaffirmed this connection to Texas’ forefather in campaign ads and garnered endorsements from a state representative, several county officials, mayors, and mayors pro tems. He soared to victory against Benny in 2012 and seemed untouchable four years later in the 2016 election.

The re-election race that Benny lost against Travis in 2012 was a sore subject with Benny, a hard one for him to discuss. It was tied to the death of Benny’s wife. He spoke of her fondly on his back porch, memories unfolding like sunflowers in the morning light.

“I did everything that I could to help him with the transition,” he said of Sheriff Travis taking office. “I had my people help him get ready for the peace officer’s exam. I did everything that I could. I didn’t have to. I could have locked the damn door and said you can have it at midnight on the first. But I didn’t. I didn’t want to impair anybody working there.”

In the 2016 election, Travis must have realized he faced the real possibility of losing his re-election bid, he warned voters that if he lost the election, Murphree would “turn back the clock and reinstitute the very same policies and procedures that put more drugs on our streets and in our schools.”

Benny replied, “I put a lot of cops in jail. I don’t like lying cops. As far as I’m concerned a lying cop is a dirty cop. … I’ve arrested robbers, murderers and child molesters. I arrested a lot of dirty police officers who did not uphold their oath of office, which every police officer takes. Will Travis has not uphold his oath of office. I know for a fact that Tracy Murphree has continually done so to this day. He still upholds his oath and spirit of office.”

A few weeks before the Republican primary in 2016, I met with Sheriff Travis for the final time at his office, unarmed and surrounded by guns. He wasn’t as jovial as he had been in previous interviews. He was on fire; he forced the photographer to stay in the waiting area and threw me into his office. He couldn’t understand why I was only focusing on the negative aspects of his life and not the positive changes he’d brought since taking office as sheriff. “I come in here every Christmas at 4 a.m. to see [ employees],” he pointed out. “They’re working on Christmas like I need to be so I come in and see them.”

He shook his head. “Yeah, no one sees that side of me. They just see that I’m a monster here.”

Travis wasn’t a monster, but many voters thought he sounded like one when he started raising questions about the circumstances of Murphree’s wife’s death. His chief deputy nearly climbed out of his chair to shut him up. Instead, he moved on to disparage Murphree for waiting a few days to tell his supervisors about a gun discharge incident in his car, a breach of protocol Murphree admitted to voters on the campaign trail.

“Nobody is saying he’s perfect,” I replied. “Nobody is saying you’re perfect. Nobody is saying you weren’t prone to making mistakes.”

Travis exploded. “Yeah, but you’re wanting to make me imperfect.”

“No, I’m not wanting to make you imperfect. That’s the problem. See, you think I’m attacking you. But all I’m doing is reporting the news. You’re running for sheriff. These are things that happened in your past that, although you think they’re simple mistakes, they’re major issues, and … have to do with integrity.”

I shifted topics in hopes of deflating his anger. I asked about his campaign finance reports and his struggles with filling them out properly. I’d been trying to discuss it with him over the past several months, but he avoided the conversation and instead tried explaining it to a former police officer who’d donated to his campaign and posts interviews with Republican candidates for the Cross Timbers Gazette, a small newspaper outlet.

“Look, he favors me,” Travis said. “They print all the good stuff of what we do down there.

“They’re overlooking important issues,” I replied.

“I’ve told them. They’re satisfied, and we’ve moved on down the road.”

“But that’s the problem. They’re biased.”

“But how can they be biased?” Travis asked. “I do a great job down there.”

“Look, [the journalist] has donated to your campaign,” I explained. “He supports you so that makes him biased. I don’t have a bone in this game. It doesn’t matter to me if you’re up there, if Weldon is up there, if Tracy is up there. I mean, don’t get me wrong, I want a sheriff with integrity, an honest one, someone who’s willing to talk to reporters when the questions are tough.”

“I gave you that folder.”

“Yeah, which means I have to talk with everyone mentioned, everyone involved. I have to talk with your ex-wife about everything.”

“No you don’t,” he replied.

“Yeah, I do.”

“No you don’t.”

Yes, I did.

Standing in Will Travis’ old office, Sheriff Muprhree felt relieved and emotional in early 2017. It had been a vicious battle on the campaign trail against Travis, and extended far beyond the sheriff’s office, notably when the death of his wife was brought into the fight. Candace Murphree had died a couple of years earlier in a freak golf cart accident leaving a festival in downtown Sangar with her husband and friends. The 34-year-old mother of four had been standing up, holding the roof of the cart when it started shaking violently. She fell off. Murphree tried to grab her. She left behind a 17-year-old son and three smaller children she shared with Murphee, ages 4, 7, and 8.

Travis told WFAA in late 2015 that he wasn’t behind the attacks against Murphree. “[I’m not in the] business of whispering things behind a person’s back or through anonymous websites and Facebook pages,” he said. “Those are the kinds of tactics my political opponents like to use, but [it’s] not my style.”

Murphree sat his children down and warned them about the rumors and lies being spread about him. He shared his frustrations on Facebook: “Many people are being told that the night my wife died, that my wife and I were intoxicated and I was driving the golf cart. People are being told that this is the reason I had to retire from the Rangers. I’m praying for those people spreading these lies. I really am.”

But now it was all behind him. After the Observer story published, exposing the darker side of Sheriff Travis’ life, Travis’ endorsement page disappeared. Former Denton County Judge Mary Horn said, “My endorsement was based initially on his job performance over the last four years. I didn’t know about everything that had taken place before that time. It’s sickening.”

Benny had known. And maybe part of him was standing there as Sheriff Murphree stood in the office, overcome with emotion. “This is what you were working for for a year,” Murphree recalls thinking three years later. “Now you got to do the job.”

His first task involved surrounding himself with good people. He tapped Barry Caver, a native East Texan and a retired Texas Ranger captain, for his assistant chief deputy. As a Ranger in the early ’90s, Caver was part of the Branch Davidian compound investigation that left four ATF agents dead, as well as 76 Branch Davidians, including 20 children and two pregnant women. Four years later, he was commanding a week-long standoff against the Republic of Texas separatists near Fort Davis. They were vowing to wage an “Alamo-style fight to the death,” according to a May 4, 1997 New York Times report. They’d been holed up in a trailer, surrounded by 300 state troopers and Texas Rangers. They had abducted two people yet agreed to lay down their weapons and come out peacefully.

Murphree established an internal affairs division and a policy manual. He then began purging his jail, establishing an accountability system that some claim is far too strict. Seventeen employees, Murphree says, were fired for criminal-related offenses. Twenty more resigned because they were under investigation for various issues. He started replacing them with veteran law enforcement officers, some from the Denton PD, yet he struggled with retaining detention officers. It’s a problem several county jails and prisons face and easy to understand. Working there feels like you’re serving time, the pay is low, and inmates are known to launch feces and piss like missiles at your face. Murphree’s opponents argue it’s due to low morale and so serious it’s forced the sheriff’s office to house prisoners elsewhere. Murphree regrets giving Travis such a hard time about it on the campaign trail and claims it has more to do with the officers’ ages (18 and 19 years old, normally) and lack of foresight regarding benefits importance.

Next he shook up the Operations Support Unit, also known as volunteer reserve deputies, took away the nice patrol cars Travis had given them, and started making them ride with full-time deputies. Two of those former OSU deputies claim they were not only saving the county $275,000 annually but also keeping the streets safe by conducting sex sting operations at area hotels. They had “built a strong cooperative interagency infrastructure, which included the Denton County District Attorney’s Office, multiple municipal law enforcement agencies, the Department of Homeland Security, the Texas Attorney General’s Office, the FBI and many non-government organizations, all committed to rescuing trafficked persons,” according to their 9-part Sheriff Muprhree removal document.

“Ruling over the Sheriff’s Office with a ‘snap-to and don’t you dare ask us questions or offer suggestions’ mentality is not leadership,” they wrote. “It is an immature and insecure attitude that suppresses the talent and free exchange of the extensive experience, knowledge and ideas which abound with the sheriff’s office.”

Murphree says he simply wanted to move the reserves toward a traditional reserve program, where they could assist full time officers or work in patrol. “The reserves ‘human trafficking’ operations were far from successful,” he wrote in a January 30 email. “They filed class C misdemeanors for attempted promotion of prostitution. Only problem is there is no crime for attempted. No charges were filed and absolutely no human trafficking victims were rescued. … Bringing Dallas prostitutes into Denton County did nothing for human trafficking. I ended it for its ineffectiveness and worked more toward the online solicitation where we actually made felony cases.”

Sheriff Murphree removes his white cowboy hat and crosses his leg, revealing his mostly bald head and the gold Ranger’s Texas star badge embroidered on his dark Justin cowboy boots. He has several pairs of cowboy boots with the star on it, and plans to work with the Justin Boot Company to get the new Denton County Sheriff badge stitched on cowboy boots for his officers. Shortly after he took office in early 2017, he changed the sheriff badge from Travis’ belt buckle to a smaller Texas star badge similar to what the Rangers proudly wear.

Inside a training room at the sheriff’s office, he compliments his opponents on their law enforcement careers. It’s late January, and his campaign is nearing its end. None of the sheriff’s seeking another term in Collin, Denton, or Wise counties have drawn a Democrat opponent. Murphree is the only one of the three sheriffs to draw two Republican challengers. Yet, he doesn’t seem bothered by it, and seems almost relieved when he says there are “no Will Travis issues” this election season.

Four years had passed since Travis threw me into his office, ready to shoot or throttle me. Last I heard he’d taken a job as a bailiff at the Dallas County Sheriff’s Department. I contacted media relations. A detective, Raul Reyna, replied after a few days, “Christian, I got a hold of Deputy Travis yesterday afternoon and he declined to be interviewed. He was very specific that he did not want to be interviewed.”

I was surprised Murphree agreed to an interview. I hadn’t spoken with him since July 2016 when I wrote Benny’s obituary for the Dallas Observer. I figured he was still upset with me over the story I published about his Facebook post threatening transgender people: “All I can say is this: If my little girl is in a public women’s restroom and a man, regardless of how he may identify, goes into the bathroom, he will then identify as a John Doe until he wakes up in whatever hospital he may be taken to. Your identity does not trump my little girl’s safety. I identify as an overprotective father that loves his kids and would do anything to protect them”

Murphree was reacting to Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick’s bathroom bill initiative. About 40,000 people were reading Murphree’s story shortly after it was posted, if I recall correctly, and nearly that many were flooding Murphee’s social media pages, upset that he was putting transgender people in more danger with his post. At first, he implied I was trying to elicit praise from my former editor, but eventually apologized for posting it, then focused on transforming the sheriff’s office into a structured Ranger-esque environment. But it didn’t keep him from the national media spotlight.

In September, when former presidential candidate Beto O’Rourke announced at the third Democratic debate, “Hell yes, we’re going to take your AR-15, your AK-47. We’re not going to allow it to be used against our fellow Americans anymore,” Murphree responded in a letter to O’Rourke on Facebook:

Dear Mr. O’Rourke,

When you say ‘we’ I hope you don’t mean me. This is one Sheriff that will never assist in your plan to trample on the 2nd Amendment rights of those I serve. I won’t help you steal personal, private, legally owned property from American Citizens. I took an oath to Preserve, Protect, and Defend the Constitution of the United States of America. A Constitution that guarantees my right to keep and bear arms. A Constitution written to protect citizens from an oppressive government. I intend to live up to that oath.

With the utmost sincerity,

Tracy Murphree

Sheriff, Denton County Texas

“Come and Take It”

It wasn’t the first time he’d called out O’Rourke. A year earlier, Murphree appeared in a segment on Fox News after O’Rourke, who was running against Sen. Ted Cruz at the time, called police the “new Jim Crow” in a speech at Prairie View A&M University in Texas. “You know there has been a war on police for the last several years,” Murphree said. “His rhetoric is divisive, insulting, and most of all it’s dangerous.” The Fox News clip soon appeared in Cruz’s campaign ad.

Shortly after O’Rourke agreed to “Come and Take It,” Murphree announced he was crafting a resolution to make Denton County a Second Amendment Sanctuary City, a place where law-abiding gun owners don’t have to live in fear of the government confiscating their guns. He wasn’t alone in his promise. As of January 13, nearly 50 Texas counties have enacted similar resolutions.

His politics isn’t the only aspect of his tenure to make headlines. The Record-Chronicle published a few articles about Murphree allegedly trying to hurry an officer-involved shooting investigator by the Rangers, which he denies, asking Denton police to investigate another officer involved shooting instead of the Rangers, which he claims he simply did because Ranger Clair Barnes was busy as the state’s witness in a capital murder trial at the courthouse across the parking lot from the sheriff’s office.

Murphree made headlines again when he chose not to release the name of the deputy who shot a wanted man. The Record-Chronicle claimed the public had a right to know. Murphree still disagrees and says he’s simply keeping his deputy (and his deputy’s family) out of harm’s way.

“I’m not releasing his name,” he reiterates in the training room. He doesn’t seem as fired up sitting across from me as he did when I first started following him on the 2016 campaign trail. Campaigning now seems more like something he’s required to do but not necessarily wanting to do. He’s been hitting the campaign trail fairly hard, attending events, forums, and luncheons around the county, fielding accusations from his opponents and trying to reassure voters that his “One riot, one Ranger” hubris was what the sheriff’s office needed.

We briefly discussed the Observer stories about his threat, and he agreed it looked bad when he read his post after the stories published. He claims he will protect a transgender person if they’re in harm’s way in Denton County. And liberals, too, and probably O’Rourke if he found his way here (though he may not like the cell he’s thrown in).

Murphree spent the next hour clearing the air and reaffirming what his opponent, Wilkinson, had said to me in an earlier interview: the conflict over the sheriff’s office was a simple disagreement over leadership approaches. Murphree stresses there hadn’t been a high standard set and no accountability when he took over. He admits they’ve taken some resistance to his policy changes. “It’s tough,” he says. “We’re tough on them.”

On the campaign trail, he’s been accused of not offering mental health counseling to officers involved in shootings, but he claims that deputies do have mandatory counseling when they shoot someone. I ask him about his reluctance to join Sheriff Skinner’s criminal interdiction unit. He counters with his office seizing $109 million in drugs/$6 million in currency and arresting dozens of pedophiles and potential human traffickers in the three years that he’s been in office without the unit’s help. They also filed the first aggravated human trafficking case in Denton County, he points out.

I’d been told Skinner isn’t a fan of Murphree’s or some of the choices he’s made. “I always follow the Golden Rule and never ever have a cross or derogatory word to say about any other Texas Sheriff,” Skinner wrote in a late January email from Washington, D.C. He was speaking at President Trump’s human trafficking summit the next morning.

This election season, Murphree seems to be following the Golden Rule as well. He says that if legal gives him the okay, he isn’t against joining Skinner’s unit.

And despite rumors to the contrary, Murphree says he has no plans for political office beyond the sheriff’s office. “I just want to be sheriff of Denton County,” he says.

After our meeting, I thought about the last night I saw Benny alive in early March 2016 at Murphree’s election night watch party at Fuzzy’s Taco Shop in Denton. Skin colored gray, almost ghostlike, Benny was standing away from the crowd that was celebrating as if the Texas Rangers had just won the World Series. He watched with approving eyes as the Sheriff-elect Murphree celebrated his win with loved ones and supporters. The hurtful words, the lies, the rumors were finally over, and Benny seemed at peace.

He’d recently reconnected with a childhood flame, Candy Harris, who reignited a spark in him that had almost faded when his wife of 40 years, Deborah, died in 2014. They’d been traveling together, enjoying what life he had left to live and sharing their adventures on Facebook. “Benny talked a lot to me about Travis,” Harris said in a recent Facebook message. “It dominated much of his final year to see justice brought against Travis.”

Four months after Murphree’s election party, Benny would succumb to cancer, sitting in his recliner on an early Saturday morning, surrounded by loved ones. “We cuddled up,” Candy recalled in an obituary I wrote for the Observer. “He said he was sorry it was almost over, just not going to make it.”

Benny’s name was mentioned several times when I met with former employees who didn’t agree with Murphree’s leadership style. Benny would be rolling over in his grave, they say, if he knew how his friend was running the sheriff’s office and retaliating against officers Benny knew. Wilkinson compared Benny’s and Murphree’s leadership styles when we met for coffee about a month before the Republican primary. A former Marine sniper trainer, the 47-year-old retired deputy doesn’t wear a white cowboy hat like Broomfield or Murphree, who rarely seems to take his off. Like Broomfield, he started as a jailer under Lucas and left 19 years later as a commander of the SWAT team and a lieutenant over the warrant section about a year after Murphree assumed control. His wife, Kady, still works in the warrant section.

“Being there through four sheriffs, I’ve got to see the politics at the sheriff’s office … from the bottom to the top,” said Wilkinson, who hails from a family of firefighters in Indiana. “As you move up through the ranks, you get to see things that are going, and you know things that are going on.”

After retiring, Wilkinson had no plans of running for office. He’d established a successful training business for church security teams, law-abiding citizens and law enforcement from around the country. “Right now my phone is exploding,” he said. “As soon as there is a church shooting, my phone explodes for a couple of months.”

Then he began receiving calls from his former colleagues, urging him to throw his name into the white cowboy hat to be the next sheriff. He officially announced his candidacy in October and claimed he would run a campaign in which he would display integrity and honesty in all his interactions, basically follow the same Golden Rule Murphree and Skinner are following. Instead, he discussed his need to create a sheriff’s office free from politics, one that serves all of Denton County and not just Republicans. A “ton of closet supporters” support him, he said. A few former sheriff deputies, an Army major, a retired Marine gunnery sergeant, a police chief, and an Austin law enforcement officer have endorsed him. “Lady Justice wears a blindfold for a reason and balancing her scales of justice is an ongoing endeavor to be sure,” he wrote on his campaign site. “With that said, I encourage those who like me and agree with my vision to vote for me, but outside of that, I ask that they stay non-political. … Again, we need to take the politics out of the Sheriff’s Office.”

At the coffee shop, he reiterated this message. “It’s about the people, not the politics,” he said.

But he is facing a political kingpin. Murphree entered the race with nearly $80,000 in his war chest, according to the Record-Chronicle. His endorsements include a long list of Republican kingpins: U.S. Congressman Dr. Michael Burgess, Texas Sen. Pat Fallon, Texas State Rep. Tan Parker, for example. U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz ignited Muprhree’s re-election kick off party with a video message:

“Sheriff Murphree is committed to the safety and security of this community. And I’m proud to endorse him in his re-election. There are many challenges facing our law enforcement officers today from inflammatory rhetoric on the left, threats to our God-given rights, and our unsecured southern border. But Sheriff Murphree understands these challenges. And he’s up to the task. Our law enforcement officers put their lives at risk, each and every day to protect the communities that they serve. Sheriff Murphree is no exception.”

In late January, Murphree touched upon many of Sen. Cruz’s points, reaffirming that his way of sheriffing has brought integrity back to the office, as Benny charged him to do before he died. “Ninety-nine percent of the men and women (who work at the sheriff’s office) have bought in to our accountability and professionalism, and there are some who haven’t, and there are some who never will,” he says. “… I’ll wait and see what the voters say. If they give me another four years, we’re going to do it the same way.”

Originally published in the March 2020 issue under the title: A Tale of Two Sheriffs